Leading Blog | Posts by Category |

Leading Blog | Posts by Category |

04.15.24

How To Rearrange Your Brain for Success

BRAD JACOBS, CEO and serial entrepreneur—United Rentals and XPO Logistics—has made and kept a few billion dollars and aims to show us how to do the same in How to Make a Few Billion Dollars. The most valuable part of the book for me was the first chapter on transforming how you use your mind. Here are ten ideas for rearranging your brain to achieve “big goals in turbulent environments where conventional thinking often fails.” Love He begins with love. Why? Love “has a lot to do with getting your brain in the right place to make good decisions. Fast-paced business environments swing between ups and downs, with many stressful interactions. Love is in an expansive emotional state that allows you to neutralize conflict and get everyone to a better place.” How do you get there? Through one-on-one gratitude conversations. Think about why other people deserve your gratitude and then sit down with them and let them know in a direct, personal manner. Expect Positive Outcomes Negative thoughts come to us quite naturally. The trick is not to let them control your thinking. Negative thoughts are often our knee-jerk reaction to a given situation. We need to acknowledge them and then reframe them in a positive light. Jacobs provides an instructive example from his family life: When we put our kids to bed at night, we’d ask them the same question many parents do: How was your day? Sometimes, we’d hear the good, sometimes the bad, and sometimes the ugly. Then we met Martin Seligman, and he suggested asking children a slightly different question: What was the happiest moment of your day? We tried it. The change was dramatic—no bad, no ugly, just the good. And maybe because our kids knew the question was coming, they kept their antennas up all day with the expectation that the happiest moment could happen at any time. What an easy create an optimistic frame of mind! What was the best part of your day? Give Yourself a Break Stop expecting unrealistic perfection from yourself and others. We sabotage ourselves all the time. Our thought processes are full of all sorts of cognitive distortions, from catastrophizing (thinking of small problems as enormous impediments) to perfectionism, where anything less than perfect execution causes intense frustration. Another cognitive distortion is dichotomous thinking (having rigid or “all-or-nothing” views). By learning to recognize these thought patterns and course-correcting accordingly, I’ve spared myself a lot of trouble. I learned, for example, to turn my internal chatter to my advantage by reframing negative thoughts as useful data rather than objective reality. If we understand that mistakes are inevitable, it will be a lot easier to “maintain your mental equilibrium as you pursue your big goals.” Expand the Possible Meditation, daydreaming, or thought experiments (the German term gedankenexperiments) can change how we relate to the world. During this time of mental calm, we can often find the best solutions, rejuvenate and become creative. Daydreaming exercises remind me that positive emotions matter, especially in chaotic business environments. When my energy is low, my favorite technique to rejuvenate and unleash creativity is to close my eyes and allow my attention to gently float in my brain. Embrace the Problem Jacobs’ mentor told him early on in his twenties as he unloaded on him with his problems, “Look, Brad, if you want to make money in the business world, You need to get used to problems, because that’s what business is. It’s actually about finding problems, embracing and even enjoying them because each problem is an opportunity to remove an obstacle and get closer to success.” Problems are an asset. The bigger your ambition, the bigger your problems. “If your initial reaction to a major setback is overwhelming frustration, that’s understandable, but it’s also counterproductive. Once you’re over that moment, pivot toward success: ‘Great! This is an opportunity for me to create a lot of value. If I can just figure out how to solve this problem, I’ll be much closer to my goal.’” Acknowledge You’re Not Perfect There are three impediments to effective leadership:

Accept your imperfections and learn from them. Cut your losses, adapt, and improve. “If you resist embracing an imperfect situation today, you might lose the opportunity to capitalize on it tomorrow.” Practical Radical Acceptance If you accept your own imperfections, you must also accept the world as it is, not as you wish it to be. Win or lose, focus on the best thing to do right now. “Radical acceptance quiets the noise created by yesterday’s decisions and today’s wishful thinking. It allows you to make a logical, forward-looking decision based on what’s likely to happen next—that and risk management are the big, relevant considerations.” Leave Judgment at the Door “The path to radical acceptance begins with non-judgmental concentration.” It allows you to focus on the issue at hand. “Non-judgmental concentration trains your brain to realize that the people and things in your life don’t exist relative to you; they simply exist. If you can take yourself out of the equation, you’ll have a much clearer view. Uncluttered by judgmentalism, you can work more efficiently; because you won’t be as distracted, and you can think more objectively, too. Think Huge To win huge, you have to think huge. “Your goals should be bigger than what you currently think you accomplish, because that can actually help you achieve those goals.” Visualize and be specific about what and when. Stay Humble Arrogance keeps you from growing—advancing. “Thinking you know it all is a trap, because you don’t—at least I don’t. If you stay humble, you’ll keep advancing.” That’s how you rearrange your brain for success. In subsequent chapters, Jacobs how to spot major trends, mergers and acquisitions (of which he has led about 500), building a team, competition, and more. I wrote this book for people who want to work their tails off, outsmart the competition, put their customers on a pedestal, and make a lot of money for their families. These goals require creativity and an enthusiasm for change—qualities at the heart of entrepreneurship. You can foster this in any size organization, whether you’re the owner of a family business or the CEO of a multibillion-dollar company to create its next billion dollars.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 07:16 AM

08.25.23

The Art of Clear Thinking

FIGHTER PILOTS must make thousands of decisions, often with incomplete information during each flight. U.S. Air Force fighter pilot and Chief of Training Systems Hasard Lee helped develop a program to boost pilots’ critical thinking skills and mental toughness to skew the odds in their favor when making these critical decisions. He passes the lessons learned on to us in The Art of Clear Thinking. Understanding how our decisions are made and how they can be improved going forward is essential with high-stakes decisions, but it is also important in our business and personal lives. The right approach to decision-making can save us a lot of regret down the road. He organizes his experience and training into a concept they call the ACE Helix. It has three parts: Access, Choose, and Execute. It is designed to bring out the best options while remaining flexible in ever-changing circumstances. 1. Assess the Problem Lee spends a lot of time explaining this step as the foundation for the success of the other two steps. “Developing a proper understanding of the problem is the first step to solving it. Our instinct is often to bypass this critical step and begin acting.” If we aren’t solving the right problem, we can make the right decision. It is important to keep the big picture in mind and not focus on just one piece of information. This is the ability to “make sense of a chaotic environment while simplifying and structuring information. This requires judgment, and judgment requires non-linear thinking. Often, our actions don’t result in a single outcome. Instead, they can lead to outsized outcomes that go beyond our imagination. They are non-linear outcomes. “For a multitude of reasons, people consistently fail to account for them, which often leads to a skewed assessment of the problem they’re facing and results in a poor decision.” These non-linear relationships are governed by power laws that can lead to exponentially greater or encompassing outcomes than we anticipated, which Lee explains in the book. “We become accustomed to how our actions are affecting a system, and then suddenly, the outcome is much different from what we were expecting. It helps if we have a broad understanding of the probable consequences of our decisions. We can adapt more quickly and accurately to changing circumstances. We can move our thinking beyond a narrow set of conditions. Lee talks about the approach they have during fighter training that all too often goes against the approach we have and certainly have experienced throughout our life. He says, “Our job wasn’t to weed them out but to coach them throughout each training event so that they could leave as the best possible pilots.” We tend to eliminate to try to cultivate the best and brightest. He adds, “We found that almost everything is coachable and correctable if identified early enough. Even supposedly intangible attributes, such as attitude, work ethic, and flying instinct, can be significantly improved if coached properly.” 2. Choose the Correct Course of Action To find the best solution, simplify. They use a technique called fast-forecasting. It is designed to build a mental model of the problem focusing on the few variables, due to strong power laws, that drive the system. This allows you to quickly approximate a ballpark solution. “We’re starting with the big-picture concept and slowly adding in detail until we have a good enough resolution to make a decision.” The key to fast-forecasting is to not get overwhelmed by the details—logic and reason are what drive the technique. Precision is often the enemy of conceptual thinking. What we’re trying to do is bring to bear the mental framework that we’ve accumulated over our lifetimes to estimate the expected value of a decision. If we instead make the problem overly complex, we lose the ability to quickly manipulate the relevant information through the lens of our concepts, principles, heuristics, and facts. Lee writes, “Creativity is one of the few resources that can provide an exponential advantage to those who are able to harness it.” Encourage creative decision-making with an effects-based approach. Start with the desired outcomes and work backward. “Breaking down the requirement into effects needed gives us at least an opportunity to explore alternative solutions.” Our desire to quickly find an answer or solution can lead us to jump to a solution that we are familiar with that might have worked in the past but is not really relevant to the current circumstance. 3. Execute Good execution requires the management of stress and, emotional control – and resilience in the face of failure. “While stress exposure can slightly increase performance for simple, well-rehearsed tasks, it severely reduces performance for tasks that require complex or flexible thinking.” Mental toughness is a skill that can be learned and improved. In fighter training, they incorporate a number of concepts into their training. Preparation is key. Mental toughness needs to be practiced until it is a subconscious reflex. They also include focus-based training. “The key to maximizing our mental resources is to focus only on what we have control over, which is the next decision to make.” Part of the training involves systematically building confidence. Confidence is not something you have, or you don’t. “Confidence is a skill that can be improved, primarily through our internal dialogue—how we talk to ourselves.” Perfectionism and focusing on our mistakes creates self-doubt, which is detrimental to high-stakes decision-making. Trainees are taught to reframe and replace negative self-talk with a successful counterexample from their past. In stressful and uncertain moments, it is important to keep your priorities your priorities. Focus on and prioritize what is important. “If there isn’t a clear vision, our minds will default toward urgent tasks.” At some point, you have to be decisive. You’ll never make the perfect decision. You can remove all uncertainty from your decision-making. When making decisions, “we’re just trying to remove the choices that are clearly not optimal.” Lee says that “when there are multiple seemingly equal choices,” he has found that “going with the riskiest viable option usually provides the greater return in value. Most people hate uncertainty, particularly when it’s combined with risk. As humans, we are biologically programmed to overestimate risk. If you’re able to overcome that mental hurdle, it becomes easy to differentiate yourself and greatly increase your odds of success.” The Art of Clear Thinking is full of great stories to illuminate the concepts and makes this business book read like a gripping novel. He shares a lot of information, so you will need to go back and reflect on how it can best be applied to your tough decisions.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 04:39 PM

07.07.23

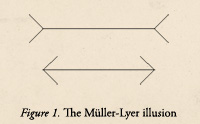

Learning to Manage the Map Paradox

WE ALL HAVE mental maps that we use to explain the world as we experience it. They also provide us with a guide to our actions. But here’s the thing. These mental maps are based on yesterday. Donald Sull calls it the Map Paradox. In The Upside of Turbulence, he writes, “In a turbulent world, people must make long-term commitments based on a mental map they know to be flawed. The paradox arises in any situation where progress requires both long-term commitments from many people and adaptation to changing circumstances.” All mental maps are static representations of a shifting situation, simplifications of a complex world made without the benefit of knowledge that will only emerge in the future. They remain always and everywhere provisional, subject to revision or rejection in light of new information. The paradox of the map demands a delicate balance between commitment and revision, stability and flexibility. Striking the balance is difficult, but possible. Of course, mental maps come in all varieties. There are mental maps that are based on values that anchor us no matter what the circumstances present us with. We all possess personal mental maps that are based on the interpretation of our experiences in life so far. These kinds of maps are often subject to revision as we grow, understand more, and gain new perspectives. All mental models are working hypotheses. Whether your mental maps are explicit or implicit, they all perform three specific functions: “They emphasize important categories, clarify relationships among variables, and suggest appropriate action.” Mental maps create biases. As we take our maps into the future—especially an uncertain future (as most futures are)—they are subject to revision when scrutinized under the light of tomorrow’s reality. Our working hypotheses “provide imperfect representations of a complex and fluid world.” The best way to avoid the Map Paradox is to continuously place your mental model up against models that are different from yours. Look for clues as to what does not support your view of the world. Consider a revolution of thought rather than simply rationalizing away the incongruities you find. Entrepreneurs often find themselves in the Map Paradox because once they build a mental model around their idea, they look for supporting information and fall prey to what they do not know. “A systematic study of three hundred start-ups found that persisting with the initial business plan was the best single predictor of failure one year after founding—nine of ten entrepreneurs who stuck to their initial business plan without revision failed.” Mental models are a necessary part of who we are. They help us to move efficiently through life, but we need to learn to manage them so we aren’t derailed by them in the reality of changing circumstances.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 10:39 AM

05.12.23

Real-Time Leadership: Creating the Space Between Stimulus and Response to Make Wise Choices

MAKING the most of every moment requires that we slow down and create some space between the challenges that are thrown at us and how we react. When faced with high-stakes challenges, we too often rely on our instincts and pattern recognition that we have developed through years of experience and plow ahead. When the challenge or opportunity is new, relying on our instincts can take us in the wrong direction. To master pivotal moments in real-time, David Noble and Carol Kauffman offer the M.O.V.E. framework in Real-Time Leadership: Find Your Winning Move When the Stakes Are High. Handling high-stakes, high-risk leadership challenges requires preparation and practice. The M.O.V.E. framework helps you to find, open, and use the space you create between the challenge and your response. The framework is described briefly this way: M: Be Mindfully Alert “Mindful Alertness in high-stakes situations means being exquisitely aware of what is needed from you as a leader at this exact moment, so you can lead in real time.” It means being “precise about and flexible with where you put your attention.” To be mindfully alert is about overcoming your instincts. If you automatically turn to your standard playbook you are not being mindfully alert. Being mindfully alert allows you to create space in real time. Every challenge you will face as a leader will involve all or some of what they call the Three Dimensions of Leadership: First is the External Dimension that refers to high-stakes that you want and need to achieve that come from your own aspirations or those that are handed to you. Next is the Internal Dimension is about your character, emotional regulation, values, and who you need to become as a leader to meet those external challenges, goals, and priorities. Finally, there is the Interpersonal Dimension is about how “to lead in the way others need, not how to lead in the way that you’d personally prefer. In any interaction, a leader must have multiple ways to respond to unlock the potential of others.” O: Generate Options Before we move into action, we increase our chance of success if we consider all of our options first. Those options revolve around four basic stances: Lean In (take an active stance), Lean Back (take an analytical stance), Lean With (collaborate with others), and Don’t Lean (be still and take in all that is around and within you to that creative wisdom can surface). The authors call it moving from willpower to waypower—generating at least four options to achieve each of your external priorities and rank them. The stance you employ needs to match the needs of the people you are with. V: Validate Your Vantage Point We need to understand our perception of the situation. Am I right? Or have I gotten it wrong? Am I seeing clearly or is my perception distorted by my own biases or by some other factor? Do I see things from other people’s perspective? Is the stance I am taking the right one? What if I used a different approach? We need to also consider if our vantage point is too high-def (fine-grained detail) or the other extreme, too grainy (just the basic details). Sometimes the situation calls for a wide view especially where creativity is called for. At other times we need to take a narrow focus. These considerations help to determine how best to spend our time. E: Engage and Effect Change Begin by communicating your intent. Boost your signals by doing only what you can do and leave the rest to others. Most leaders will find that their job is not to be the specialist, but the generalist. The authors also address the Real-time challenges of stepping into a new role. The key, they say, is changing your vantage point. Once you have gained clarity on your new vantage point, you can then begin to apply the rest of the MOVE framework. Adjust your behavior to the new relationship dynamics required by your new role. Let people get to know you as much as you can. Remember, too, “You must identify with the whole organization, not just the parts you’re comfortable or familiar with.” Depending on your situation (and time), you may not need to apply the MOVE framework in order. Think of the four elements as a checklist and when one area doesn’t check out, start there. For example, ask yourself, “Do I feel that I have several options I can call on to achieve my priorities, and not just depend on my default approach?” If not, start working there to broaden your options. Great leaders “create a space between stimulus and response and exploit that space—whether it’s seconds, hours, or longer—to make wise choices. The most extraordinary leaders live in that space.” They are centered. It takes practice and commitment to get there. When a group of monks were frustrated because they felt their powers of concentration and mindfulness had plateaued, even though they practiced nonstop, they approached the Dali Lama for advice. The Dali Lama paused for a moment before playfully replying, “I can say that over the past forty years of practice, I have noticed … some improvement.”

Posted by Michael McKinney at 06:31 AM

02.26.21

Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know

RETHINKING can cause uncertainty. Make us uncomfortable. Feel uneasy. It can threaten our identities. But rethinking can also help us find solutions to old problems, deepen our perspective, release us from inherited dogma and other people’s opinions, and understand how our closely held values relate and are applied to our changing environment. Adam Grant challenges us to Think Again—to question what we think we know. “Unfortunately, when it comes to our own knowledge and opinions, we often favor feeling right over being right.” Grant’s colleague Phil Tetlock discovered that when we think and talk (and scan social media), we tend to slip into the mindsets of three different professions: preachers, prosecutors, and politicians. “The risk is that we become so wrapped up in preaching that we’re right, prosecuting others who are wrong, and politicking for support that we don’t bother to rethink our own views.” (Grant offers a short Think Again quiz on his website.) The approach to ideas and opinions that we need to be gravitating to is the scientist mindset. It is a mindset of curiosity and a search for truth rather than becoming defensive, offensive, or appeasing.

Rethinking is not a question of how smart you are. “The brighter you are, the harder it can be to see your own limitations. Being good at thinking can make us worse at rethinking.” What does matter is how curious and actively open-minded you are. Actively in the sense that we are searching for reasons why we might be wrong. A key to rethinking is being able to detach yourself from your beliefs. This takes two forms: “detaching your present from your past and detaching your opinions from your identity.” Who you are should be a question of what you value, not what you believe. Values are your core principles in life—they might be excellence and generosity, freedom and fairness, or security and integrity. Basing your identity on these kinds of principles enables you to remain open-minded about the best ways to advance them. It is quite common for differences of opinion to turn into a relational conflict—personal and emotional—filled with animosity and vindictiveness. Task conflict is often desirable in order to get to the best answer. “The absence of conflict is not harmony, it’s apathy.” When a clash gets personal and emotional, we become self-righteous preachers of our own views, spiteful prosecutors of the other side, or single-minded politicians who dismiss opinions that don’t come from our side. While it’s nice to have people around us that agree with us, successful people need a challenge network—people we trust that can point out blind spots, doubt our knowledge and be humble about our expertise. In short, people who will question us and hold us accountable for rethinking our perspectives. Wilbur Wright once wrote, “Honest argument is merely a process of mutually picking the beams and motes out of each other’s eyes so both can see clearly.” Grant notes that “research suggests that we want people with dissimilar traits and backgrounds but similar principles. Diversity of personality and experience brings fresh ideas for rethinking and complementary skills for new ways of doing.” In a debate, it is best to begin with finding common ground. It’s a dance. “When we concede that someone else has made a good point, we signal that we’re not preachers, prosecutors, or politicians trying to advance an agenda. We’re scientists trying to get to the truth.” At the same time, keep your argument simple. Too many, and you will dilute the power of each and every one. “We don’t have to convince them that we’re right—we just need to open their minds to the possibility that they might be wrong.” When we know that we might not really know, rather than investigating, “we become mental contortionists, twisting and turning until we find an angle of vision that keeps our current views intact.” And we can become quite hostile. No surprise there. It’s hard to get others to change. It’s better to help them find their own reason to change. And the best way to do that is to listen—ask questions. What we have to avoid is the righting reflex—“the desire to fix problems and offer answers.” There are a good number of issues in the world where there is more going on than we know. The issues are complex and not binary—yes or no. Admitting the complexity of an issue is often a sign of credibility. And skeptics are not deniers. They are curious. If you find yourself saying _____ is always good or _____ is never bad, you may be a member of an idea [or personality] cult. Appreciating complexity reminds us that no behavior is always effective and that all cures have unintended consequences. Grant gives us many more reasons to rethink what we think than I have covered here. His concern is that by reading the book, we don’t close the book on the issue of rethinking. The book brings awareness to our human nature, but it doesn’t make us do anything about it. It’s easy to look at our loosely held beliefs and rethink them. The challenge is to rethink those deeply held ideas and beliefs that tend to divide us—especially those ideas that we have blindly accepted from others. We—collectively—have outsourced far too much of our thinking. It’s time to think again.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 07:51 AM

12.15.20

Uncharted: How to Navigate the Future

PREDICTION has never been easy – or that accurate. Over and over again, forecasts and models fail us. And when they do, they won’t go away because the agenda behind them lives on. As a model or a forecast is designed to do, we become “recruited into an army of believers.” “The more we believe, the less we question,” says Margaret Heffernan. In Uncharted: How to Navigate the Future, she writes that “Overwhelmed with complexity, we seek simplification and too quickly reach for binary perspectives, just at the moment when we need broader ones.” How true. We crave certainty in a world that remains ambiguous. In an outstanding first chapter—False Profits—she reviews the work of three economic forecasters and the shortcomings and consequences of each. Forecasts and models are useful if they get you thinking, but only if we see them for what they are—propaganda.

Our past informs our present and future, but it can’t predict it. History, especially our personal history, defines a trajectory and provides us with probabilities. It tells us how we tend to react to what life throws at us, but we also have the capacity to learn and grow and change. New experiences shape us.

Believing that his history always repeats itself can lead to “blindness and blunder.”

Much of what she is talking about here defines the year 2020. So, if we can’t predict the future, what can we do? First, we can experiment more. In a time of crisis, we need to know more. We need to experiment. Experiments are an “antidote to helplessness or passivity. They set us on paths that reveal new knowledge and choices.” We can develop scenarios to “identify and test how and where the future and the present meet.” Different from experiments that “reveal immediate internal features of a complex system, scenarios explore where the internal organization meets the external environment, where uncertainties lurk beyond anyone’s control.” Scenario planning always surfaces conflict and there is always a moment when everything seems to fall apart. But getting the conflict out in the open, constructively, is crucial; it’s how and when people start to acknowledge and consider alternative perspectives. Third, we need to think like an artist. Artists think for themselves. They pay attention. Notice more. And then they let it sit—simmer, filter, distill, digest. Then they act. The only way to know if you are on to something is to start. I liked the phrase: “moving in and out of focus, trying to get a feel for something that doesn’t exist yet.” To have insights that are relevant to life requires having a life, one rich in experiences, and the time to internalize them. Fourth, think beyond. Start a Cathedral Project. Cathedral projects are unpredictable from the beginning. “They are destined to last longer than a human lifetime, to adapt to changing tastes and technologies, to endure long into the future as symbols of faith and human imagination.” They are also full of experiments making them “intrinsically, ambiguous, uncertain, and full of risk.” They attract brilliant minds because “the scale of their aspiration ensures that, instead of being passive victims of the future, they are actively involved in making it.” Imagination, creativity, compassion, generosity, variety, meaning, faith, and courage: what makes the world unpredictable are the same strengths that make each of us unique and human. Accepting uncertainty means embracing these as robust talents to be used, not flaws to be eliminated.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 05:11 PM

11.27.20

The Hidden Habits of Genius

WHO and what is a genius? The label gets thrown around a lot. Are you a genius? Probably not. But then, most of us are not. However, you can learn to think like one. Craig Wright teaches a class at Yale on the nature of genius. He distills all of that work into his book with a hopeful title, The Hidden Habits of Genius: Beyond Talent, IQ, and Grit—Unlocking the Secrets of Greatness. Perhaps there is something we can learn from true geniuses that will help us perform better ourselves. I like the definition of a genius provided by German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer: “A person of talent hits a target that no one else can hit; a person of genius hits a target that no one else can see.” Wright defines a genius as “a person of extraordinary mental powers whose original works or insights change society in some significant way for good or for ill across cultures and across time.” Geniuses work hard, but it’s not the hard work—the 10,000 hours of practice—that is the secret. “Practice may make the old perfect, but it does not produce innovation.” Talent may be the impetus, but hard work moves it along. To get to the top, it seems “you must max out both.” IQ tests can’t predict the next genius or a person’s potential. Some who have done well academically, like Marie Curie, Sigmund Freud, and Sergey Brin, went on to do remarkable things. But others we look up to today, like Einstein, Edison, Steve Jobs, and Picasso, did poorly in school. What about prodigies—young people who possess talents far beyond their years? Not really. “The difference is that geniuses create. They change the world through original thinking that alters the actions and values of society. Prodigies merely mimic. Childlike creativity plays a part. Picasso said, “Every child is an artist. The problem is to remain an artist as we grow up…. When I was a child, I could paint like Rafael, but it took me a lifetime to paint like a child.” “From Einstein’s mental play with images emerged his famous thought experiments. Einstein was able to imagine the world as a child while keeping apposite scientific information in mind.” Geniuses are lifelong learning addicts. “Students may receive information and learn methodologies in school, but the game changers of this world acquire the vast majority of what they know over time and on their own.” They learn what they need to know. What about passion? “If our passions drive us in ways that ultimately change society, that change is a mark of genius.” Not all passion leads to genius. Geniuses see things differently. They “cannot accept the world as described to them. Each sees a world asunder and cannot rest until things are put right.” Some geniuses are rebels, but not all rebels are geniuses—no matter how remarkable they may seem in the present. Some rebels, misfits, and troublemakers are just that. Not geniuses, but rebels, misfits, and troublemakers—people that just want their own way or push their own agenda. Wright correctly asks, “What is it that all of us believe today that some genius will disprove tomorrow?” We should be more careful pushing our biases and opinions. “Most rebels are not geniuses.” A person that changes the course of history need not be a genius, but rather someone who saw an opportunity and took it. Some people we presently regard as geniuses are clever and creative, but they are not geniuses. Aesop observed in his fable, The Fox and the Hedgehog, that “the fox knows many small things, while the hedgehog knows one big thing.” Wright says, be the fox. Develop a wide range of knowledge, perspectives, and skills. Cross-train. “The more broadly based the information in mind, the more likely that disparate ideas are combined.” Jeff Bezos observed, “The outsized discoveries—the ‘non-linear’ ones—are highly likely to require wandering.” “The lesson for all of us,” says Wright, “stay nimble.” Imagine the end and work backwards. Think opposite. Again, Bezos instructs: “You see a new technology, or there’s something out there, … and you work backwards from a solution to find the appropriate problem.” Wright says, “the more a person can exploit the contradictions of life, the greater his or her potential for genius.” To coax out your best ideas, relax. “If you need a fresh idea, go for a walk, or jog, or simply get into a relaxing conveyance so as to allow your mind to range more freely.” Then concentrate. Like a genius, “create a daily routine for yourself that comes with a four-wall safe zone for constructive concentration…. At the end of the day, you alone are responsible for synthesizing that information and producing something.” Could we use more geniuses? Well, yes. But what we really need are people who learn to think like a genius. Not the pandering and the misuse of statistics to push an agenda that has become so prevalent. We need people who will take a measured approach and contribute constructive ideas that will benefit the rest of us.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 02:31 PM

11.23.20

Think For Yourself

A GREAT IRONY of our time is that even as we are more informed, we are thinking less. We outsource our thinking. We rely on others to think for us. And we do almost unconsciously, by default, without thinking. As the change around us adds complexity and an overwhelming number of choices, we naturally defer to experts to focus our attention on what matters. In Think for Yourself, Harvard University lecturer Vikram Mansharamani cautions that “by outsourcing our focus to them, we willfully let them take control over our field of vision, blind to what they leave out.” He cautions, “At the very least, we should think about, and ideally ask about what other variables might be worth considering.” When we listen to or limit our options to the criteria of a similar set of experts, it will limit our options, filter our information, and the soundness of our decisions. When “our decision frames are set by others, and we forget to keep track of what options and factors we ignore, [we open] ourselves up to unnecessary risks and missed opportunities” and unsubstantiated fear and perspectives. When an expert focuses on their specialization, they often lose the broader perspective that has a significant bearing on the issue in question. “The key is to step back and ask: What are you losing when you narrow your option set?” Focus May Work Against Us While focus has its place, focusing is a process of filtering out and ignoring. When we do, we miss out on some things and see more of what we are focusing on. “Focus increases confidence while clouding judgment.” Fundamentally, the Peter Principle is about focus. It’s about how managers tend to focus too much on how a person is doing in their current job as the means through which to evaluate their potential for their next job. But when you stop to think about it, that doesn’t make a ton of sense. Evaluation criteria should be based on future roles. It may mean that some people who are performing poorly in their current position may blossom if promoted. We’ve heard it said that the cure is worse than the disease. “By focusing intensely in one domain, we often fail to see how our actions may create the very problem we are seeking to avoid. We need to step back, zoom out, and look at the whole system rather than just its parts. The sad reality is that many of our supposed solutions are compounding the problems.” The bottom line is that we are all dependent on others to some extent; it’s a fact of modern life. But this dependence need not translate into blind obedience. As we turn to those who can help, we must remember their limitations and appreciate other perspectives. Triangulate Perspectives We need to take the time to gather other perspectives—to triangulate unique points of view. A perspective is, by definition, incomplete. Each has its limitations. We owe it to ourselves to get several points of view to expand our context. On a personal level, empathizing and seeing your circumstances in a bigger context can be useful. It’s helped dampen my exuberance when I’m on top of the world, and also boosted my spirits during tough times. Having a broader context on your own perspective is critical in uncertain times. In navigating uncertainty, Mansharamani reminds us that “probing, sensing, and responding are key activities. It’s a dot-connecting exercise, not a dot-generating one.” Experts are among the least successful predictors in times of massive uncertainty. They often think they know more than they actually do and therefore exhibit more confidence than is warranted. Hubris tends to affect their objectivity, particularly when they become the go-to thinkers to help others who by definition are admittedly confused. The result: a significant number of very visible expert predictions have gone embarrassingly wrong…. It was often developments outside of their domain that derailed their predictions. Experts are more reliable in complicated environments and where there is a clear cause-and-effect relationship. Mansharamani says we need to “come up with a new way to engage experts.” To begin, we need to “abandon our devotion to depth and reintroduce a greater focus on breadth.” Economist Noreena Hertz said in a 2010 TED Talk: We’ve become addicted to experts. We’ve become addicted to their certainty, their assuredness, their definitiveness, and in the process, we’ve ceded our responsibility, substituting our intellect and our intelligence for their supposed words of wisdom. We’ve surrendered our power, trading off our discomfort with uncertainty for the illusion that they provide. Navigating uncertainty requires that we learn to triangulate unique points of view and connect the dots. “It takes an independent, external, and less-focused perspective to connect the dots in a conclusive way.” Rather than going out and getting a “second first opinion, we need to get “a true, unadulterated, independent second opinion.” We can help ourselves by exposing ourselves to different points of view and experiences and becoming perpetually curious rather than accepting a single perspective. “The idea of being broad enough to contextualize information is critical; it helps to generate awareness that there are those who know more than we do and allow us to place the inputs of experts and specialists in perspective.” The future belongs to those who can think for themselves.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 01:50 PM

11.11.20

The Myth of Experience

WE LEARN from experience. We’d be silly not to. But the question becomes, what are we learning? Experience is a powerful teacher, and therein lies the problem. We may think we are gaining wisdom, when in fact we are just reinforcing the wrong lesson just as powerfully. In The Myth of Experience, Emre Soyer and Robin Hogarth write that “while experience still leads to learning, there is no guarantee that its lessons accurately represent the reality of a situation.” We naturally assume that what we see is all there is. Experience rarely gives us a complete picture of the situations we face. What we think is reality is just what we can see. And this is true in certain circumstances—in learning environments that are kind. In kind learning environments like cycling and tennis, “decision makers receive abundant, immediate, and accurate feedback on their actions and the rules of the game remain largely constant.” If everything we did was like tennis or cycling, then the lessons we gain from experience would be fairly reliable. But many/most experiences in life are not like that. Much of the time, our circumstances are not that reliable. Our activities fall into the category of wicked learning environments, “where experience is constantly subject to a variety of filters and distortions.” That means what we think we are experiencing does not correspond with reality. These circumstances “may not only fail to represent a given situation accurately but also constantly feed us a convincing illusion. The rules can change suddenly and dramatically, rendering our institutions obsolete.” So, what do we do? Rejecting what we think we know can be very difficult. Two Crucial Questions You Need to Ask Recognizing that what we are experiencing may not be connected to reality is the first step. Next, ask two questions about what you are experiencing: What’s missing? Is there something important missing from my experience that I need to uncover is I hope to fully understand what is happening? And What’s irrelevant? What irrelevant details are present in my experience that I need to ignore to avoid being distracted from what is happening? How We Learn from Experience Our experiences quickly become part of a story we tell ourselves. And these stories become the basis for the judgments and predictions we make. They help us to form cause-and-effect relationships. While these stories can be beneficial to us, they can also be too simple to adequately capture the reality of the situation. And we can see stories where none exist—no cause-and-effect. When we tell this story enough, it can be hard to accept anything else. If not handled with care, our experience can make us believe in the wrong causes, expect unrealistic consequences, evaluate performances inadequately, make bad investments, reward or punish the wrong people, and fail to prepare us for future risks. Worse, we may not even notice that we are acting upon faulty stories and fail to revise them in a timely and appropriate way. As a result, we may end up solving the wrong problems, using inadequate methods, and failing to achieve our objectives. And we need to be careful about learning from the experiences of others. We’ve all seen and read them: The 8 Things Billionaires Do Every Day. What the Most Productive Do Before Breakfast. 10 Common Traits of Effective Leaders. These lists can be helpful in that they get us to think about our habits and give us insight into what’s possible, but how accurate are they. I mean, did all of the people interviewed diligently do everything on the list? Are these things they do the result of their success or the cause of their success. Are they predictive? What about people who did these things and failed?

If we are to learn the right lessons from experience we need to ask ourselves, what’s missing and what’s irrelevant from our situation. And The Myth of Experience illuminates the way.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 05:43 PM

08.21.20

Touching the Jaguar: How to Transform Your Fear into Action

FACING OUR FEARS is often what is standing between us and success. Touching the Jaguar is a cathartic memoir by John Perkins about confronting the things you fear to make the necessary changes in your life. In this memoir, he touches on the value of altering your perception to change your reality. It’s a valuable lesson expressed in a new way. While working in the Amazon, a shaman told him about touching the jaguar: The jaguar stands on a Perception Bridge “that could convey us from a reality based on preconceived ideas and values to a reality based on new ideas and values. If we are scared off by that jaguar, held back by things we’d been taught in the past or our fear of change, for example, we would not get past the jaguar and cross the bridge. If, on the other hand, we touched the jaguar, recognized the voices, teachings, values, or other barriers that stood in our way, confronted them and altered them, we are empowered to take the actions necessary to cross the bridge into a new reality.” We live with two realities. There is reality itself, and then there is what we perceive it to be. By crossing the perception bridge, we are taken to a new perspective. We can find compassion and empathy from other perspectives. We receive the energy to move forward and take positive action. We can ask what we might do to help others cross the Perception Bridge. By touching the jaguar, we are “recognizing that human reality is molded by our perceptions and that to change ourselves or our world, we must break through the barriers that imprison us in old ways of thinking and acting. If we run from or deny our fears, they will hound us. By confronting them, we take their power.”

Posted by Michael McKinney at 12:01 AM

06.10.20

How to Think Like a Rocket Scientist

FORMER rocket scientist turned law professor, Ozan Varol, believes that while we can’t all be rocket scientists, we can all learn to think like one. Think Like a Rocket Scientist is about creativity and critical thinking—two skills in short supply today. We all encounter complex and unfamiliar problems in our daily lives. Those who can tackle these problems—without clear guidelines and with the clock ticking—enjoy an extraordinary advantage. Creativity comes naturally to us, but we are educated out of it in favor of certainty. Critical thinking, while valued theoretically, is not taught because we prefer the ease of conformity and the prepackaged answers we can accept from others. Think Like a Rocket Scientist is a content-rich and very practical book. Varol offers nine principles in three stages to help us to reacquire and build our creativity and critical thinking muscles. In the first stage, we learn how to ignite our thinking. Stage two is focused on propelling the ideas we created in stage one. In the final stage, we learn why the final ingredient for unlocking our full potential includes both success and failure.

1. Flying in the Face of Uncertainty Bertrand Russell wrote that “the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.” We crave certainty to the point of making sure and true what isn’t certain at all. We do so at our own peril. “Where certainty ends, progress begins.” “The great obstacle to discovering,” historian Daniel J. Boorstin writes, “was not ignorance but the illusion of knowledge.” The pretense of knowledge closes our ears and shuts off incoming educational signals from outside sources. Certainty blinds us to our own paralysis. The more we speak our version of the truth, preferable with passion and exaggerated hand gestures, the more our egos inflate to the size of skyscrapers, concealing what’s underneath. Because of uncertainties, rocket scientists build in redundancies and margins of safety. “Think about it: Where are the redundancies in your own life?” To deal with uncertainties, we must begin walking before we see a clear path. “Start walking because it is the only way forward.” 2. Reasoning from First Principles There are all kinds of narratives floating around based on assumptions, and when we pick one, they become who we are. First-Principles thinking takes us back to the beginning and questioning the assumptions. “The French philosopher and scientist René Descartes described it as systematically doubting everything you can possibly doubt, until you’re left with unquestionable truths. When you apply first-principles thinking, you go from what James Carse calls a finite player, someone playing within boundaries, to an infinite player, someone playing with boundaries. Ask yourself, Why are they making that choice? It’s not because they’re stupid. It’s not because they’re wrong and you’re right. It’s because they see something that you’re missing. It’s because they believe something you don’t believe. 3. A Mind at Play A mind at play is a curious mind. Thought experiments ask “what if” questions. “Thought experiments construct a parallel universe in which things work differently. Through thought experiments, we transcend everyday thinking and evolve from passive observers to active interveners in our reality.” Varol says, compare apples and oranges. Get bored more often. Boredom allows our mind to tune out of the external and allows our mind to wander and daydream. If we don’t take the time to think—if we don’t pause, understand, and deliberate—we can’t find wisdom or form new ideas. As author William Deresiewicz explains, “My first thought is never my best thought. My first thought is always someone else’s; it’s always what I’ve already heard about the subject, always the conventional wisdom. Moonshot Thinking Moonshot thinking is taking a leap of faith. Incremental change modifies the status quo. Moonshot thinking allows for exponential change and upending the status quo. The story we choose to tell ourselves about our capabilities is just that a choice. And like every other choice, we can change it. Until we push beyond our cognitive limits and stretch the boundaries of what we consider practical, we can’t discover the invisible rules that are holding us back.

5. What If We Sent Two Rovers Instead of One? Questions matter. Make sure you’re solving the right problem. Peter Attia, a physician and renowned expert on human longevity, said: When people are looking for the “right answers,” they are almost always asking tactical questions. By focusing on the strategy, this allows you to be much more malleable with the tactics. Varol adds: Once you move from the what to the why—once you frame the problem broadly in terms of what you’re trying to do instead of your favored solution—you’ll discover other possibilities in the peripheries. 6. The Power of Flip-Flopping Confirmation bias is alive and well primarily because it feels good, and it takes the work out of really thinking. While scientists are trained to be objective, even rocket scientists have a hard time thinking like rocket scientists. “No one comes equipped with a critical-thinking chip that diminishes the human tendency to let personal beliefs distort the facts.” Opinions are hard to reassess. “When your beliefs and your identity are one and the same, changing your mind means changing your identity—which is why disagreements often turn into existential death matches.” If the mind anticipates a single, that’s what the eye will see. Before announcing a working hypothesis, ask yourself, what are my preconceptions? What do I believe to be true? Also ask, do I really want this particular hypothesis to be true? If so, be very careful. Be very careful. 7. Test as You Fly, Fly as You Test A test where the results are predetermined is not a test. “In a proper test, the goal isn’t to discover everything that can go right. Rather, the goal is to discover everything that can go wrong and to find the breaking point.” Rocket scientists try to break the spacecraft on earth before it breaks in space. Find the breaking points. When astronaut Chris Hadfield returned from a successful mission, if everything had gone as planned, he responded, “The truth is that nothing went as we’d planned, but everything was within the scope of what we prepared for.”

8. Nothing Succeeds Like Failure Rocket scientists don’t celebrate failure, nor do they demonize it. They take a more balanced approach. Nor do they fail-fast. The stakes are just too high. Their mantra is to learn fast. We often assume failure has an endpoint. But failure isn’t a bug to get out of our system until success arrives. Failure is the feature. If we don’t develop a habit of failing regularly, we court catastrophe. 9. Nothing Fails Like Success Success conceals failures. Sometimes success is pure luck. Without failures to learn from, we must learn from our successes. Success is the wolf in sheep’s clothing. It drives a wedge between appearance and reality. When we succeed, we believe everything went according to plan. We ignore the warning signs and the necessity for change. With each success, we grow more confident and up the ante. We pay a lot of lip service to critical thinking, yet it is a rare commodity. Think Like a Rocket Scientist is an essential read for anyone wanting to develop critical thinking skills or to mature their thinking.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 07:57 PM

04.27.20

Cognitive Reappraisal for Wild Success

EXTREME adventurers have to perform at their best every time, or there might not be another time. They must be able to execute a plan under pressure. The same qualities that help them succeed will help any leader perform at a higher level and especially in a crisis situation. Wild Success by Amy Posey and Kevin Vallely illustrates seven leadership lessons we can learn from the harrowing experiences of extreme athletes. They are cognitive reappraisal, grit, learning from feedback, finding your spark, innovation, resilience, and building balance. I want to focus on a critical, but often difficult skill that we all need to develop: cognitive reappraisal. When you are looking at danger, uncertainty, and understandable fear, you need to be able to get perspective on what you’re facing. And when things go wrong, this discipline is even more critical. Posey and Valley introduce the experience of one of the best big wave surfers in the world, Australian Mark Mathews. Before Mark faces a dangerous wave like the slab wave he’s about to ride, “he performs a set pre-surf ritual to put his mind into focus. It’s something he does every time. ‘Fear is a big part of what I do,’ he says, ‘so dealing with it effectively is critical to my performance.’ Using simple breathing techniques to slow his mind down, Mark concentrates on feelings of excitement rather than anxiety, while reflecting on why he is doing what he is doing.” But on this day in 2016, Mark attempts to escape the wave, but the wave picked him up and slammed him feet first into the reef. Rushed to the hospital, the doctors find that the force of the blow has dislocated his knee, fractured his chin, ruptured his anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, and ripped through his artery and nerve. They doubt they can save his leg. But with some luck they do, and he is treated for three months in the hospital. It looks like his career is over. But it isn’t. His ambitions have only grown. “What allows Mark to have the mental wherewithal to claw back from catastrophic injury and still have the fortitude to remain committed to the very thing that has hurt him so badly?” Cognitive reappraisal. Cognitive reappraisal is our ability to consciously manage our emotional experiences and responses to a setback or challenge and transform the negative emotions we feel into more positive ones. Cognitive reappraisal lets us not only acknowledge and reduce our emotional response to a negative situation, but it also changes our perspective on that situation by letting us take a step back and add a positive spin to whatever challenge we’re facing. Building this ability takes practice. Every setback is an opportunity to develop this mindset until it becomes a habit. For Mark, his “ability to positively reframe a situation both on and off the waves has come with lots of practice, and this practice developed a habit of cognitive reappraisal that served him well when he needed it most.” A habit of reframing a negative situation actually rewires your brain. A study by Columbia University professor Kevin Ochsner and his team found that when those who reframed a negative situation in a positive light, “their prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain integral to one’s cognitive behavior and emotional self-regulation, was activated by their reframing of the situation, while their amygdala, the area of the brain associated with fear and anxiety, saw a reduction in activity.” Negative events happen to us all. It’s normal to have an adverse emotional reaction—anger, hurt, self-doubt—at first. But if you can recognize the emotion in the moment—the shallow breathing, sweaty palms, an upset stomach—and make a choice to put cognitive reappraisal into action, you will take much of the stress out of the situation and allow for your creativity and to take hold and move forward in a more emotionally intelligent way. If we miss these symptoms [of stress] at the early stage, we quickly move into something called the emotional “point of no return,” where your emotions become fully activated, and reappraisal becomes exceptionally difficult. Practicing this anticipatory regulation during small and low-stakes stressors allows you to understand your own point of no return and [be better able to pull yourself] back from it. Cognitive reappraisal is a simple idea but very difficult to put into practice in the heat of the moment. But with some intentional practice, you can make it a habit that will serve you well in stressful and negative situations.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 07:07 AM

09.04.19

The Optimist’s Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age

HOW DO YOU get people to think ahead? In a time characterized by wide-ranging change, we need to think through the consequences of what we have wrought. We need to think ahead. It is reckless not to. Since we can’t predict the future it makes it hard for us to think about the future. It should come as no surprise that our view of the the future is often misguided. In 1920, British economist Arthur Cecil Pigou described our often skewed view of the future as our “defective telescope.” In The Optimist’s Telescope, author Bina Venkataraman suggests that we need to cultivate a “radical strain of optimism” and a sense of collective agency that would motivate “more people to make choices today for the sake of the future, whether it’s how they vote, eat, use energy, or influence others.” An “optimist’s telescope” so to speak. Looking beyond the noise is key to thinking ahead. “Urgency and convenience are dictators of decisions large and small. We are frequently distracted from our future selves and the future of our society by what we need to accomplish now.” Our society is designed around quick wins because that’s what we want. “The conditions we have created in our culture, businesses, and communities work against foresight.” Rewards are given for the quick win. We need foresight. Foresight combines what we know with the humility to know that we don’t know it all and be ready for the possibilities. And that requires a little imagination. Venkataraman eloquently states, “We try too hard to know the exact future and do too little to be ready for its many possibilities.” Venkataraman offers countless examples of how individuals and organizations have defied instant gratification and instead taken the long view. When one investment firm saw a stock price fall they wisely avoided a knee-jerk reaction. “They avoided distractions of the moment by returning like a broken record to their original rationale for believing in the stock. You might call this a North Star tactic, calling on people in an organization to habitually look up from daily minutiae to reorient themselves to their ultimate destination.” At a Stanford Director’s College in 2016, Roger Dunbar, chair of the Silicon Valley Bank, told Venkataraman that “when he hears company executives or board members responding to short-term noise with outsize reactions, he likes to pretend he is lost. He’ll ask CEOs at board meetings, ‘What was our long-term strategy again?’ as if he has forgotten it. Sometimes, he says, company leaders suffer from being too smart—analyzing every piece of data that come their way—instead of asking simple but pivotal questions. It can help, in his view, to have a board member who is not afraid of sounding naïve or even a touch senile.” It helps too to look past typical metrics to see what is actually happening long-term. Dan Honig, a political scientist at the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, believes that “metrics can be useful when an organization has a simple, concrete goal such as building a road. The trick is for the measure to be tightly linked to what the organization actually wants to accomplish. For the more complex undertakings of organizations, however, numeric targets are often far removed from actual goals and more likely to deceive. In those instances, Honig says, managers are better off using their judgment to evaluate progress. It’s a common mistake for organizations to attach simple metrics to nuanced goals such as educating children, reforming the justice system, or growing an innovative business.” It would be a bitter irony to remain entranced by myopic metrics, gearing ourselves up to hit immediate targets at a time when technology and our economy are evolving to privilege humans for being visionary, empathetic, nuanced, and strategic. In the future, the human edge is going to come from what we value and from our judgment, not from going head-to-head with machines to parse facts. On a personal level, we too can learn to measure ourselves by more meaningful metrics than what we have achieved in the moment. From her research, Venkataraman has extracted five key lessons to help us think ahead and stay the course: 1. Look Beyond Near-Term Targets “We can avoid being distracted by short-term noise and cultivate patience by measuring more than immediate results.” Instead of looking at snapshots, reflect on long-term goals. 2. Stoke the Imagination “We can boost our ability to envision the range of possibilities that lie ahead.” Allow time to imagine future risks and rewards and then visualizing how we can successfully navigate those futures. 3. Create Immediate Rewards for Future Goals “We can find ways to make what’s best for us over time pay off in the present” or “seek programs that offer immediate allure but are designed for our long-term interest.” In an example she shares about Toyota, they found a way to use the insights gained from long-term research on current production. “They found a way to create immediate rewards that made their sacrifices for the sake of future products seem worth it now to company leaders and investors.” 4. Direct Attention Away from Immediate Urges “We can reengineer cultural and environmental cues that condition us for urgency and instant gratification.” Avoid temptations. Where urgency rules, create systems that interrupt the momentum to create space to consider the decision. 5. Demand and Design Better Institutions “We can create practices, laws, and institutions that foster insight.” Look for solutions that encourage us to look ahead. Of course, institutions are made up of people, so we only need to look to ourselves first rather than trying to regulate foresight. Ultimately, Venkataraman believes we need to think like stewards or as she puts it, “keepers of shared heirlooms.” Heirlooms carry with them the “notion that future generations matter to the present generation, and that past generations will matter to the future.” Furthermore, “with an heirloom, each generation is both a steward and a user. When we pass on an heirloom, we don’t prescribe what each steward must do with it. Instead, we leave options open to the next generation.” It’s a good way to view our responsibility to think ahead.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 05:30 AM

03.20.19

Get Savvy

FAKE NEWS is not a new phenomenon. From the beginning of time, people have played loose with the truth in order to get what they want. Trust too, has waxed and waned over the millennia. It’s not new. People have always had to be on the lookout for fake news. And much has gotten through our filters over the centuries and has negatively impacted the assumptions we take for granted today. Perhaps what if different today is our ability to so quickly and persuasively disseminate it through technology. It makes the task of discerning fact from fiction so much harder. So much information is coming at us about things we know very little about and in our rush to form an opinion we easily become susceptible to misinformation and other people’s agendas. As Jonathan Swift wrote in 1710, “Falsehood flies and the truth comes limping after.” We believe what we want to believe. This is the subject of Savvy: Navigating Fake Companies, Fake Leaders, and Fake News in the Post-Truth Era by the husband and wife team Shiv B. Singh and Rohini Luthra. The stark reality is that we have entered ... a new post-trust era, in which telling truth from opinion, and separating fact from outright fabrications, requires us to be on guard, intensely aware of the ways in which we are being played, and how we are unwittingly contributing to the problem. Fakery has not only pervaded politics, it has made deeper inroads into business and our personal lives.  “Savvy is about understanding the role we (as consumers of information) play in succumbing to and propagating fakeness. Just as we have technology glitches so too do we have human glitches in the way we process information.” So the authors catalog some of the ways we readily deceive ourselves and play into fake news. These “glitches” are well presented and deal with the problem of fake news at its source. Repetitions Make the Truth If we hear a lie enough times, we begin to believe it. “We all know perfectly well that simply hearing something over and over again doesn’t mean it is truth, but we fall for this persuasive tactic anyway. Why?” We move toward things that are familiar to us because they are comfortable. “The more often we her something, the more familiar it becomes, and familiarity breeds trust.” We Want to Belong The desire to belong is strong. Not only does this foster groupthink, but it most often creates a toxic us versus them mentality “often leading to the demonization of the ‘other’ and contributing to discrimination and sometimes violence.” They encourage us to welcome dissenting opinions. Respect those with different viewpoints. We Want to Be Right “We want to be right, and we look for information that supports our existing beliefs.” This is known as confirmation bias. Because of this bias, when we try to convince others of the truth, they most often become more convinced of their own position. The more you try to convince someone else of your view the more entrenched they become of their own. The best approach is to find some common ground on which to build a basis for trust. Humility is in order. Overconfidence in our own opinion can cloud our judgment and lead us to marginalize others. We Bow to Authority We tend to trust people in authority. In my view, we should always respect those in authority because of our own self-respect. While respect is a choice, leaders must also know that they need to behave in a way that is deserving of respect. That said, we shouldn’t blindly follow leaders. “Assess a leader’s credibility, expertise, experience, and integrity.” We Blindly Trust Artificial Intelligence Perhaps that is an overstatement, but the authors are right in saying, “Rapidly advancing innovations are providing new capabilities that require us to give serious thought to the degree of trust we should place in the companies and governmental bodies that will be deploying them, and in the technologies themselves.” Again, it’s not the technologies, it the people who use them. Some will use them to greatly enhance the quality of our life and others will use them to control others. We need to discern the difference. And we should never blame the computer or use it as an excuse for the disrespect of human beings. Computers are programmed no matter how human they seem.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 12:36 PM

03.04.19

11 Shifts Every Leader Needs to Make

TO GET FROM where we are to where we want to be requires a shift in our thinking. When our thinking shifts in an area, our perspective changes, and new opportunities become visible. We serve people differently. In Leadershift, John Maxwell states, “every advance you make as a leader will require a Leadershift that changes the way you think, act, and lead.” Shifts in thinking require that you see a bigger picture, rethink your perspective, and understand your context. Your leadership potential depends on these shifts. It’s is unlikely that you would make all of these shifts at once. Some will happen gradually. Some will happen almost overnight. Some will come naturally to you and others will seem counterintuitive. We’re all different but we all need to make these shifts. Essentially they all boil down to making the shift from me to we. Maxwell suggests eleven leadershifts that have helped him grow as a leader. Here are a few ideas from each of the leadershifts he describes: Leadershift #1 Soloist to Conductor – The Focus Shift You can’t do it alone. Leadership is not a solo practice. Of course, working with others has its challenges. A big part of this shift is changing your focus from receiving to giving. Adding value every day without keeping score. “As leaders, we must stop wishing and start working. Instead of looking for the ‘secret sauce’ of success, we must start sowing seeds of success.” Leadershift #2 Goals to Growth – The Personal Development Shift Rather than focusing on goals, focus on growth. “Goals helped me do better, but growth helped me become better.” Begin on the inside. “Growth on the inside fuels growth on the outside.” You can’t do everything, so focus on four areas: attitude, developing strong relationships, your leadership, and equipping others to carry on without you. To become more growth-oriented, you need to embrace change, be teachable (humble), learn from failure, connect with other growth-minded people, believe in yourself, and understand that real wisdom is acquired and applied over time. Leadershift #3 Perks to Price – The Cost Shift Great leadership isn’t about control, the income or the corner office. It’s about sacrifice. Great leadership costs us something. American missionary Adoniram Judson is rumored to have said, “There is no success without sacrifice. If you succeed without sacrifice, it is because someone has suffered before you. If you sacrifice without success, it is because someone will succeed after you.” Great leaders go first. “What sets great leaders apart from all other leaders is this: they act before others, and they do more than others. Great leaders face their uncertainty and doubt, and they move through it to pave the way for others.” Leadershift #4 Pleasing People to Challenging People – The Relational Shift You can please some of the people some of the time, but you can’t please all of the people all of the time. But if you want the best out of people, you have to challenge them. “You have to put doing what’s right for your people and organization ahead of what feels right for you.” This means keeping your eye on the big picture. Sometimes you have to have tough conversations, but you must balance care with candor. Leadershift #5 Maintaining to Creating – The Abundance Shift Maintaining isn’t always easy, but it is the easiest mindset to slip into. It’s not about change for change sake, but it’s about “can we do better?” Create a creative environment where people gather ideas and value multiple perspectives. “Being inflexible and sticking to my plan put a lid on me and my organization.” Larry Stockstill said, “I live on the other side of ‘yes.’ That’s where I find abundance and opportunity. It’s where I become a better and bigger self. The opportunity of a lifetime must be seized within the lifetime of the opportunity. So I try to say ‘yes’ whenever I can.” Leadershift #6 Ladder Climbing to Ladder Building – The Reproduction Shift This shift is about equipping others. We being with ladder climbing (How high can I go?), then we shift to ladder holding (How high will others go with a little help?), then ladder extending (How high will others go with a lot of help?) to finally, ladder building (Can I help them build their own ladder?). “If you want learners to follow directions, you only need to provide the what. If you want them to lead others and give directions, they must also have the why.” Leadershift #7 Directing to Connecting – The Communication Shift You must learn to connect with people to be the best leader you can be. To move from directing people—talking, ready answers, your way—to connecting—listening, asking, empowering. Be a person people can trust. Lift others up. “When you interact with others as a leader, what is your mindset? Is your intention to correct them or connect with them?” Leadershift #8 Team Uniformity to Team Diversity – The Improvement Shift If everyone around you thinks like you, you need to expand your network. A diverse team will fill in gaps in knowledge, perspective, and experience. “Malcolm Forbes said diversity is the art of thinking independently together.” Leadershift #9 Positional Authority to Moral Authority – The Influence Shift Moral authority is not about position it’s about who you are. People follow moral authority before they follow positional authority. Maxwell lists four areas a leader needs to develop to have moral authority: competence, courage, consistency, and character. “Every leader who possesses moral authority has had to stand alone at some point in time. Such moments make leaders.” Leadershift #10 Trained Leaders to Transformational Leaders – The Impact Shift Maxwell believes that if you only make one shift in your leadership, this is the one because it “will bring the greatest change to your life and the lives of those around you.” Transformational leaders inspire others to become more. But that’s because they have worked to become more themselves. “If you want to see positive changes in your world, the first person you must change is you. As leaders, you and I have to be changed to bring change. We teach what we know, but we reproduce who we are.” Leadershift #11 Career to Calling – The Passion Shift This is the shift from just doing a job to do what you are gifted to do. Aristotle wrote, “Where our talents and the needs of the world cross, there lies our vocation.” Your calling is not about you. “A calling moves us from the center of everything in our world to becoming the channel through which good things come to others.”

Posted by Michael McKinney at 10:30 AM

12.25.18

Hyperfocus: How to Take Control of Your Mind

THERE ARE LIMITS to our attention. There is only so much we can focus on at any given time. So it becomes critical what we allow in our attentional space if we want to get anywhere in life. (And heads up. Your attentional space shrinks as you age—but your mind wanders less.) When we try to cram too much into our attentional space, we experience attention overload. When we do that we forget things because we didn’t leave enough space for what we originally intended to do. What is going on in our attentional space is the subject of Chris Bailey’s Hyperfocus. Bailey shows us how we can use our limited attentional space intelligently and deliberately so that we can focus more deeply and think more clearly. Hyperfocus happens when we consciously expand our attention to fill our attentional space. It is when we are the most productive—and happy. So, how do we enter hyperfocus mode? Distractions are distracting because they are more attractive than what we are focusing on. We have to plan in advance to remove them. Distractions are costly. Put the phone down. Don’t check the emails. “It takes an average of twenty-five minutes to resume working on an activity after we’re interrupted, and before resuming that activity, we work on an average of 2.26 other tasks.” Not good. Our smartphones rob our attention probably more than anything else. Bailey offers this great advice: “Resist the urge to tap around on your smartphone when you’re waiting in line at the grocery store, walking to the coffee shop, or in the bathroom. Use these small breaks to reflect on what you’re doing, to recharge, and to consider alternative approaches to your work and life.” Reflection is one of the biggest gifts we can give ourselves. And then we have to deal with the natural wandering of our mind by continually and consciously refocusing. It also helps to plan to hyperfocus for a predetermined length of time. “Setting specific intentions can double or triple your odds of success.” Bailey has a whole chapter on taming distractions and offers techniques to help us with all of this.